This second long-overdue post is a talk I gave a few months ago. As a practice for presenting our dissertations in September, we were asked to present any paper relevant to the course. Anything at all. So I found one about pigeons. Enjoy!

Note: I've pasted in text, which has resulted in some amusing font issues. I haven't worked out how to fix them. Such is life.

My paper is ‘The

mysterious spotted green pigeon and its relation to the dodo and its kindred’,

by Heupink, Grouw and Lambert. They used ancient DNA analysis to find out a bit

more about a very mysterious bird and shoehorn in a bit about the dodo, because

dodos are cool. But I think that the pigeon itself is an interesting

story in its own right.

The spotted green

pigeon, Caloenas maculata, is

extinct. It was described in 1783 based on two specimens.

One was collected by

Sir Joseph Banks, one by General Thomas Davies. But then the Banks specimen was lost...

... Leaving us with just one. And it lives in the World Museum...

... in Liverpool. In fact, its other common name is the Liverpool pigeon.

Unfortunately, nobody knows where either specimen originally came from.

But

both Banks and Davies did most of their collecting in Oceania, so probably from

there.

Here's a

reconstruction. It's a fairly standard tropical pigeon. It could definitely fly.

Apparently its short, rounded wings suggest that it lived on islands. But to

infer more about it, it would be helpful to know what its closest relatives are.

Unfortunately,

the spotted green has rather jumped around the pigeon tree. The big group

containing European pigeons is Columbinae at the top. Raphinae has the huge

diversity of tropical pigeons.

Based

on morphology, the spotted green has been placed somewhere in Ptilinopini,

sister to the imperial, mountain or fruit pigeons.

On the other hand,

it’s also very similar to the Nicobar pigeon, which sits in the extended dodo clade (green). Some think the spotted green is a sister species to the

Nicobar; others even think they’re conspecific, with the spotted green being a juvenile or otherwise ‘abnormal’ Nicobar.

What

technique can help resolve taxonomic questions based only on morphology? DNA

analysis! Which is where Heupink and colleagues come in.

The

team managed to extract DNA from two feathers. Because that one remaining

specimen is a couple of hundred years old, they used ancient DNA techniques,

which included lots of contamination precautions and lots of controls.

Unfortunately,

the first PCR failed to amplify anything. The fragments they had were too short

to make it through. So they made some changes to their methods, having mostly

just followed a kit the first time round.

There

were two key improvements, both on the final step of DNA extraction, when you

bind the DNA to a membrane and wash away impurities.

First,

they used a binding buffer with more isopropanol. This encouraged the shorter

DNA molecules to actually bind. Another group had already tried this and it

worked for them. The

second thing was to wash with the buffer in the kit multiple times, and also

with phenol. This removed more PCR inhibitors, quantitatively and

qualitatively.

So

finally...

They

succeeded in getting detectable, amplifiable DNA! Unfortunately...

The

fragments were super short. Like less than 30 base pairs long.

The

quantity was really low.

And

for one of the two feathers, the DNA was super fragmented too.

But

at least they had DNA. The

idea had been to analyse a barcode from the mitochondrial 12S gene. Their

reference dataset was over a hundred 12S sequences from pigeons, downloaded from GenBank.

But

the spotted green fragments were too short for a typical barcode...

... so the team

designed three

mini-barcodes instead. These

turned out to work really well. They sequenced successfully and consistently,

and...

... a

BLAST search said

that the sequences came from an unknown pigeon, which was exactly what they

wanted.

Using

the mini-barcodes, and all of the reference sequences, they built a maximum

likelihood tree for each feather, and they were pretty much identical, which

was a relief. All

but one of the other taxa ended up where they were expected to - the pigeon

tree isn’t completely stable yet, but this was consistent with previous

findings. But the only support metric they’ve used there is bootstrap, which

sticks in my mind from the cladistics course as something you shouldn’t rely on

too hard. It would have been nice to see another measure there too.

But

anyway, This is a zoom in on one of them. the spotted green pigeon comes out

closest to the Nicobar with high bootstrap support (it's out of 100), for what it’s worth. They

are very similar after all.

But

could it be the same as the Nicobar? Is it really a different species? I’m sure you all

remember how tricky species delimitation can be, and we can’t look at

within-species variation for the spotted green because we only have one of

them. But Hupink’s team did look at simple pairwise identity - how similar the

spotted green mini-barcodes were to sequences for other taxa.

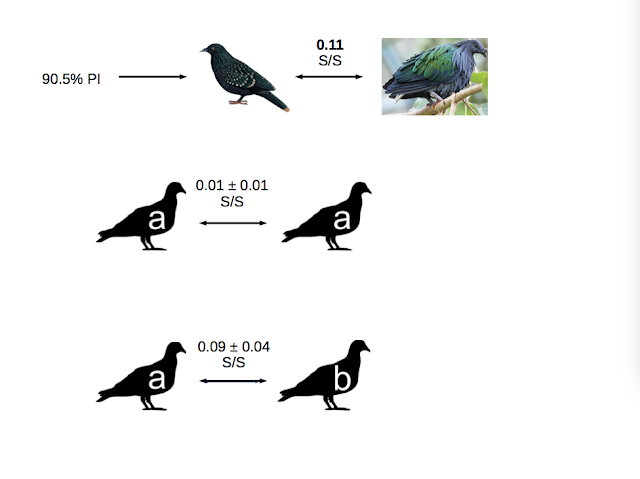

There

was an average of 90.5% pairwise identity between the spotted green and the

Nicobar. This translated to about 0.11 substitutions per site. The average

difference within species was 0.01 substitutions per site, and the average

difference between species of the same genus was 0.09.

T-tests

showed that the spotted-Nicobar average was significantly different from

within-species, but not from within-genus.

So, the spotted green

shares a genus with the Nicobar pigeon but is different enough to be its own

species.

But that’s not quite

the end. There is actually a third species in the genus: Caloenas canacorum, the Kanaka pigeon. Why didn’t the team include

it? They talked about this.

The Kanaka pigeon is

extinct, and is only known from a handful of subfossils found on New Caledonia

and Tonga: hot, humid, beautiful places that turn DNA into soup. The boundaries of ancient

DNA keep being pushed, but it’s not there yet.

Also, the Nicobar is

bigger than the spotted green, and the Kanaka is bigger than the Nicobar, so we

can be pretty sure it’s not the same species as the spotted green. Leaving it

out doesn’t increase confusion over what the spotted green is.

Now remember that Caloenas is in the extended dodo clade.

The dodo and its also-extinct sister taxon, the Rodrigues solitaire, form the

subfamily Raphinae.

Apart

from Raphinae (in the box), all species in this clade fly and come from Oceania. They’re all

tropical island-hoppers. People

guessed this from the spotted green pigeon’s morphology, but now we have

phylogenetic evidence to back that up. Adding

another Oceanic island-hopper also adds some more support to the island-hopping

hypothesis of how the dodo and Rodrigues solitaire got to their islands - that

their ancestors could fly until they arrived.

It

also reinforces how morphologically weird Raphinae is, and how much morphological

variation the clade shows. In fact, it’s probably not surprising that it was so

hard to place the spotted green by morphology.

So,

the paper starts with a lone specimen of unknown providence and uses ancient

DNA to confirm that it was an island-hopper from Oceania and a proper species

in its own right. On top of that, they contributed to DNA extraction

methodology and say a bit about the dodo.

References

Dabney, J. et al. Complete mitochondrial genome sequence of a Middle Pleistocene cave bear reconstructed from ultrashort DNA fragments. PNAS 110, 15758–15763 (2013).

Heupink, T.

H., van Grouw, H. & Lambert, D. M. The mysterious Spotted Green Pigeon and its relation to the Dodo and its kindred. BMC Evolutionary Biology 14, 136 (2014).

Pereira, S. L., Johnson, K. P., Clayton, D. H. & Baker, A. J. Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA

Sequences Support a Cretaceous Origin of Columbiformes and a Dispersal-Driven

Radiation in the Paleogene. Syst Biol 56, 656–672 (2007).

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/.

(Accessed: 6th May 2017)

Image credits by slide