A few months ago, during one of my wonderfully quiet early mornings in the library, I did a double take as I spotted two mice running up and down the aisles. I've since seen traps. Clearly there are more mice around than the staff would like. Today I made a rare afternoon visit and, sitting at a desk, something small and brown on the carpet caught my eye. I was secretly happy to have seen a mouse again. But on closer inspection, it was no mouse!

It was a robin!

Unfortunately, it didn't look like it was going to get out any time soon. The open window was tall and narrow, and after the robin fluttered past it a few times I got the impression it was deliberately not going through. I reported it to the very excited librarians and, as I left, one was considering using her sandwich as bait. I will check in tomorrow to see what happened.

UPDATE: The next day I asked what had happened, and the staff had managed to get it out without much trouble. Fast forward to the 16th of September, my next visit, and the robin was back again. I don't think it was trapped. I think it was clever.

Wednesday, 30 August 2017

Tuesday, 29 August 2017

More grave goods: blowflies

While awaiting feedback on last week's draft, I've mostly been collecting references and formatting. But I also went back down to the lab to take some pretty pictures. The entomologist has finished identifying the fly puparia from one of the grave samples: they turned out to be Protophormia terraenovae, the northern blowfly. They eat bodies! It confirms that there really was a body, which isn't exactly groundbreaking but is nice to know.

The entomologist wants to do some high-tech imaging of some of the best preserved puparia later on. But for my project, I decided it would be nice to have some simple photos just to show what they look like. Not many people see blowfly puparia, and even fewer up close. I borrowed a lovely microscope and camera setup from the schistosomiasis people, who use it to photograph the little water snails that carry that nasty nasty parasite. Here are two of the best in the finished figure:

The lower one actually has a little fly face poking out! The two flat discs are its eyes, and the little lumpy bit southwest of them is the proboscis. It looks like it was starting to emerge when it died, because that's the part of the puparium that they hatch out of. I don't know enough about flies to say more than that. But it was quite a surprise!

Blowflies only feed on carcasses, so the puparia can't have just ended up in the soil long after the person was buried. They must have been there from the time of burial. This site is at least 100 years old, possibly 200, making this a very old fly indeed.

The entomologist wants to do some high-tech imaging of some of the best preserved puparia later on. But for my project, I decided it would be nice to have some simple photos just to show what they look like. Not many people see blowfly puparia, and even fewer up close. I borrowed a lovely microscope and camera setup from the schistosomiasis people, who use it to photograph the little water snails that carry that nasty nasty parasite. Here are two of the best in the finished figure:

The lower one actually has a little fly face poking out! The two flat discs are its eyes, and the little lumpy bit southwest of them is the proboscis. It looks like it was starting to emerge when it died, because that's the part of the puparium that they hatch out of. I don't know enough about flies to say more than that. But it was quite a surprise!

Blowflies only feed on carcasses, so the puparia can't have just ended up in the soil long after the person was buried. They must have been there from the time of burial. This site is at least 100 years old, possibly 200, making this a very old fly indeed.

Friday, 25 August 2017

Drafts

|

| A girafft. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Giraffe_standing.jpg |

For the last few weeks, I've been working increasingly hard and long to get a draft of my thesis done. I've done so many analyses that didn't work, come to so many conclusions that turned out to be irrelevant or wrong, and agonised over some beautiful graphs that didn't actually show anything helpful.

|

| Like those graphs. Beauty is ephemeral. |

But yesterday, a draft was done. I sent it off at about two and was out of the building by three thirty. Today I've been working on fiddly formatting and referencing bits, satisfyingly monotonous admin that requires very little thinking, and it has been great. The end is near!

Wednesday, 23 August 2017

A pot of snake worms

All was quiet yesterday afternoon. My usually busy office was empty but for me, the two single-office researchers and the curator on my floor were away and nobody was using the labs. So when a visiting retired scientist came wandering up looking for somebody, he came to me. He said he was in the process of slimming down his collection of parasitological paraphernalia and wanted to donate some specimens to the museum. He handed over an ancient hummus pot filled with specimen jars:

Each containing snake worms: parasitic worms from snakes. Needless to say, these are rather difficult to come by. They're now on the curator's desk, hopefully destined for the vaults.

Each containing snake worms: parasitic worms from snakes. Needless to say, these are rather difficult to come by. They're now on the curator's desk, hopefully destined for the vaults.

Sunday, 13 August 2017

Big pretty moth

|

| Fingertip for scale. I have normal-sized fingers. |

|

| Accidental flash probably blinded the poor thing. |

A quick Internet tells me it was probably a swallow-tailed moth, otherwise known as a 'flying post-it note': https://www.ukmoths.org.uk/top-20/ (number 9)

Thursday, 10 August 2017

Spreadsheet time

Today I made and understood a really complicated spreadsheet:

I also realised I'd put my pants on inside-out this morning. It all balances out.

I also realised I'd put my pants on inside-out this morning. It all balances out.

Tuesday, 8 August 2017

Hello Hope

In December, the NHM staff gathered for a final set of photos with Dippy the Diplodocus, before he was taken down for his tour around the country. Since then, Hinze Hall has been closed for refurbishment. It finally opened again just a couple of weeks ago, with a new star attraction hanging from the ceiling: a blue whale named Hope (or nearly, rumour has it, 'Drippy'). She'd been in the whale hall for decades but is now in much finer form, having undergone some serious conservation work and fitted to a brand new frame, in a much more lifelike pose.

To welcome her in, the staff gathered once more:

I like her a lot. Dippy is lovely, but she reminds us of our responsibility to the world. We aren't just spectators.

I've been posting a lot over the past couple of days, catching up on things. This is because I've had a lot of downtime while waiting for endless computer processes to run. They might all have been done by now, but I keep making mistakes, so everything iterates. I'm starting to worry about time. The end is near.

To welcome her in, the staff gathered once more:

I like her a lot. Dippy is lovely, but she reminds us of our responsibility to the world. We aren't just spectators.

I've been posting a lot over the past couple of days, catching up on things. This is because I've had a lot of downtime while waiting for endless computer processes to run. They might all have been done by now, but I keep making mistakes, so everything iterates. I'm starting to worry about time. The end is near.

The mysterious spotted green pigeon

This second long-overdue post is a talk I gave a few months ago. As a practice for presenting our dissertations in September, we were asked to present any paper relevant to the course. Anything at all. So I found one about pigeons. Enjoy!

Note: I've pasted in text, which has resulted in some amusing font issues. I haven't worked out how to fix them. Such is life.

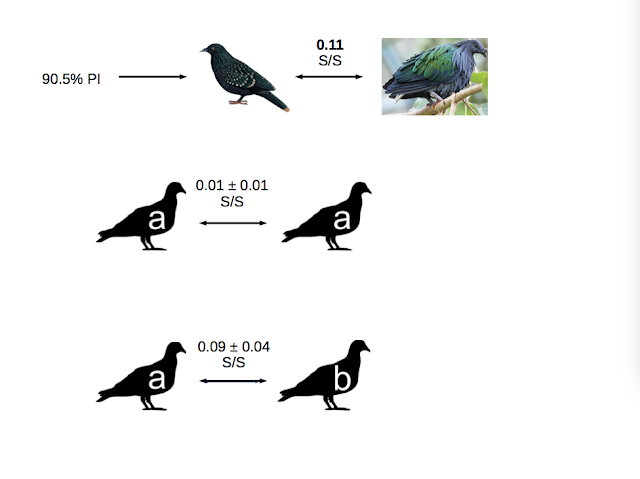

My paper is ‘The mysterious spotted green pigeon and its relation to the dodo and its kindred’, by Heupink, Grouw and Lambert. They used ancient DNA analysis to find out a bit more about a very mysterious bird and shoehorn in a bit about the dodo, because dodos are cool. But I think that the pigeon itself is an interesting story in its own right.

On the other hand,

it’s also very similar to the Nicobar pigeon, which sits in the extended dodo clade (green). Some think the spotted green is a sister species to the

Nicobar; others even think they’re conspecific, with the spotted green being a juvenile or otherwise ‘abnormal’ Nicobar.

But

could it be the same as the Nicobar? Is it really a different species? I’m sure you all

remember how tricky species delimitation can be, and we can’t look at

within-species variation for the spotted green because we only have one of

them. But Hupink’s team did look at simple pairwise identity - how similar the

spotted green mini-barcodes were to sequences for other taxa.

But that’s not quite

the end. There is actually a third species in the genus: Caloenas canacorum, the Kanaka pigeon. Why didn’t the team include

it? They talked about this.

References

Dabney, J. et al. Complete mitochondrial genome sequence of a Middle Pleistocene cave bear reconstructed from ultrashort DNA fragments. PNAS 110, 15758–15763 (2013). Heupink, T.

H., van Grouw, H. & Lambert, D. M. The mysterious Spotted Green Pigeon and its relation to the Dodo and its kindred. BMC Evolutionary Biology 14, 136 (2014).

Pereira, S. L., Johnson, K. P., Clayton, D. H. & Baker, A. J. Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA Sequences Support a Cretaceous Origin of Columbiformes and a Dispersal-Driven Radiation in the Paleogene. Syst Biol 56, 656–672 (2007).

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/. (Accessed: 6th May 2017)

Image credits by slide

Note: I've pasted in text, which has resulted in some amusing font issues. I haven't worked out how to fix them. Such is life.

My paper is ‘The mysterious spotted green pigeon and its relation to the dodo and its kindred’, by Heupink, Grouw and Lambert. They used ancient DNA analysis to find out a bit more about a very mysterious bird and shoehorn in a bit about the dodo, because dodos are cool. But I think that the pigeon itself is an interesting story in its own right.

The spotted green

pigeon, Caloenas maculata, is

extinct. It was described in 1783 based on two specimens.

One was collected by

Sir Joseph Banks, one by General Thomas Davies. But then the Banks specimen was lost...

... Leaving us with just one. And it lives in the World Museum...

... in Liverpool. In fact, its other common name is the Liverpool pigeon.

Unfortunately, nobody knows where either specimen originally came from.

But

both Banks and Davies did most of their collecting in Oceania, so probably from

there.

Here's a

reconstruction. It's a fairly standard tropical pigeon. It could definitely fly.

Apparently its short, rounded wings suggest that it lived on islands. But to

infer more about it, it would be helpful to know what its closest relatives are.

Unfortunately,

the spotted green has rather jumped around the pigeon tree. The big group

containing European pigeons is Columbinae at the top. Raphinae has the huge

diversity of tropical pigeons.

Based

on morphology, the spotted green has been placed somewhere in Ptilinopini,

sister to the imperial, mountain or fruit pigeons.

What

technique can help resolve taxonomic questions based only on morphology? DNA

analysis! Which is where Heupink and colleagues come in.

The

team managed to extract DNA from two feathers. Because that one remaining

specimen is a couple of hundred years old, they used ancient DNA techniques,

which included lots of contamination precautions and lots of controls.

Unfortunately,

the first PCR failed to amplify anything. The fragments they had were too short

to make it through. So they made some changes to their methods, having mostly

just followed a kit the first time round.

There

were two key improvements, both on the final step of DNA extraction, when you

bind the DNA to a membrane and wash away impurities.

First,

they used a binding buffer with more isopropanol. This encouraged the shorter

DNA molecules to actually bind. Another group had already tried this and it

worked for them. The

second thing was to wash with the buffer in the kit multiple times, and also

with phenol. This removed more PCR inhibitors, quantitatively and

qualitatively.

So

finally...

They

succeeded in getting detectable, amplifiable DNA! Unfortunately...

The

fragments were super short. Like less than 30 base pairs long.

The

quantity was really low.

And

for one of the two feathers, the DNA was super fragmented too.

But

at least they had DNA. The

idea had been to analyse a barcode from the mitochondrial 12S gene. Their

reference dataset was over a hundred 12S sequences from pigeons, downloaded from GenBank.

But the spotted green fragments were too short for a typical barcode...

But the spotted green fragments were too short for a typical barcode...

... so the team

designed three

mini-barcodes instead. These

turned out to work really well. They sequenced successfully and consistently,

and...

... a

BLAST search said

that the sequences came from an unknown pigeon, which was exactly what they

wanted.

Using

the mini-barcodes, and all of the reference sequences, they built a maximum

likelihood tree for each feather, and they were pretty much identical, which

was a relief. All

but one of the other taxa ended up where they were expected to - the pigeon

tree isn’t completely stable yet, but this was consistent with previous

findings. But the only support metric they’ve used there is bootstrap, which

sticks in my mind from the cladistics course as something you shouldn’t rely on

too hard. It would have been nice to see another measure there too.

But

anyway, This is a zoom in on one of them. the spotted green pigeon comes out

closest to the Nicobar with high bootstrap support (it's out of 100), for what it’s worth. They

are very similar after all.

There

was an average of 90.5% pairwise identity between the spotted green and the

Nicobar. This translated to about 0.11 substitutions per site. The average

difference within species was 0.01 substitutions per site, and the average

difference between species of the same genus was 0.09.

T-tests

showed that the spotted-Nicobar average was significantly different from

within-species, but not from within-genus.

So, the spotted green

shares a genus with the Nicobar pigeon but is different enough to be its own

species.

The Kanaka pigeon is

extinct, and is only known from a handful of subfossils found on New Caledonia

and Tonga: hot, humid, beautiful places that turn DNA into soup. The boundaries of ancient

DNA keep being pushed, but it’s not there yet.

Also, the Nicobar is

bigger than the spotted green, and the Kanaka is bigger than the Nicobar, so we

can be pretty sure it’s not the same species as the spotted green. Leaving it

out doesn’t increase confusion over what the spotted green is.

Now remember that Caloenas is in the extended dodo clade.

The dodo and its also-extinct sister taxon, the Rodrigues solitaire, form the

subfamily Raphinae.

Apart

from Raphinae (in the box), all species in this clade fly and come from Oceania. They’re all

tropical island-hoppers. People

guessed this from the spotted green pigeon’s morphology, but now we have

phylogenetic evidence to back that up. Adding

another Oceanic island-hopper also adds some more support to the island-hopping

hypothesis of how the dodo and Rodrigues solitaire got to their islands - that

their ancestors could fly until they arrived.

It

also reinforces how morphologically weird Raphinae is, and how much morphological

variation the clade shows. In fact, it’s probably not surprising that it was so

hard to place the spotted green by morphology.

So,

the paper starts with a lone specimen of unknown providence and uses ancient

DNA to confirm that it was an island-hopper from Oceania and a proper species

in its own right. On top of that, they contributed to DNA extraction

methodology and say a bit about the dodo.

References

Dabney, J. et al. Complete mitochondrial genome sequence of a Middle Pleistocene cave bear reconstructed from ultrashort DNA fragments. PNAS 110, 15758–15763 (2013). Heupink, T.

H., van Grouw, H. & Lambert, D. M. The mysterious Spotted Green Pigeon and its relation to the Dodo and its kindred. BMC Evolutionary Biology 14, 136 (2014).

Pereira, S. L., Johnson, K. P., Clayton, D. H. & Baker, A. J. Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA Sequences Support a Cretaceous Origin of Columbiformes and a Dispersal-Driven Radiation in the Paleogene. Syst Biol 56, 656–672 (2007).

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/. (Accessed: 6th May 2017)

Image credits by slide

1 Specimen

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Caloenas_maculata_Clemency_Fisher.jpg

2 Extinct logo http://www.iucnredlist.org/

3 Sir Joseph Banks htps://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6e/Joseph_Banks_1773_Reynolds.jpg

5 The Beatles https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Beatles_ad_1965_just_the_beatles_crop.jpg

6 Oceania map https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/43/Oceania%2C_broad_%28orthographic_projection%29.svg/2000px-Oceania%2C_broad_%28orthographic_projection%29.svg.png

7 Caloenas maculata reconstruction del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., & Sargatal, J. eds. 2002. Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 7. Jacamars to Woodpeckers. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona

8 Columba livida http://s0.geograph.org.uk/geophotos/01/30/95/1309587_3b1c324c.jpg Caloenas nicobarica https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/32/Nicobar_Pigeon_RWD2.jpg Ptilinopus jambu https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4f/Jambu_Fruit_Dove_2010.jpg

18 Barcode https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3a/Example_barcode.svg/2000px-Example_barcode.svg.png

21 BLAST logo https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi

Pigeon silhouette http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Columba_livia_Luc_Viatour.jpg

22 Maximum Likelihood tree, from Heupink et al. (2014)

23 Raphus cucullatus https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/9b/Frohawk_Dodo.png Pezophaps solitaria https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/47/Pezophaps_solitaria.png

29 Island in Tonga https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/af/%27Atata_Island.JPG

2 Extinct logo http://www.iucnredlist.org/

3 Sir Joseph Banks htps://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6e/Joseph_Banks_1773_Reynolds.jpg

5 The Beatles https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Beatles_ad_1965_just_the_beatles_crop.jpg

6 Oceania map https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/43/Oceania%2C_broad_%28orthographic_projection%29.svg/2000px-Oceania%2C_broad_%28orthographic_projection%29.svg.png

7 Caloenas maculata reconstruction del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., & Sargatal, J. eds. 2002. Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 7. Jacamars to Woodpeckers. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona

8 Columba livida http://s0.geograph.org.uk/geophotos/01/30/95/1309587_3b1c324c.jpg Caloenas nicobarica https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/32/Nicobar_Pigeon_RWD2.jpg Ptilinopus jambu https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4f/Jambu_Fruit_Dove_2010.jpg

18 Barcode https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3a/Example_barcode.svg/2000px-Example_barcode.svg.png

21 BLAST logo https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi

Pigeon silhouette http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Columba_livia_Luc_Viatour.jpg

22 Maximum Likelihood tree, from Heupink et al. (2014)

23 Raphus cucullatus https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/9b/Frohawk_Dodo.png Pezophaps solitaria https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/47/Pezophaps_solitaria.png

29 Island in Tonga https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/af/%27Atata_Island.JPG

31 Didunculus strigirostris

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/cf/Didunculus_strigirostris.jpg

Goura scheepmakeri https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/69/Goura_scheepmakeri_sclaterii_1_Luc_Viatour.jpg

32 Map, modified from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f2/World_pacific_0001.svg/2000px-World_pacific_0001.svg.png

Goura scheepmakeri https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/69/Goura_scheepmakeri_sclaterii_1_Luc_Viatour.jpg

32 Map, modified from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f2/World_pacific_0001.svg/2000px-World_pacific_0001.svg.png

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)