For the second and final day of curation experience, I was working with a palaeontology curator and someone, I think, from the pest management team who was nevertheless also a palaeontologist. Aptly, the day's activities involved pest management and

general organising of fossil tetrapods.

In the morning we finished off what yesterday's students had worked on. We were in the museum's quarantine area, inspecting a new collection that had been donated, funnily enough, by someone who once taught me. It was boxes and boxes of Triassic synapsids, the group that gave rise to mammals, including little Diictoton that would have looked something like this:

The boxes were very well

organised, though we had to swap out most of the packing material. Over

the long term, things like fleece wrap and South African newspapers from

the 70s don't make good packaging because they can break down, release

chemicals that can harm specimens (most paper is acidic) or be eaten by

pests. Another part of the job was looking for said pests. They might not be able to eat fossils, but just having them in the same building as more edible materials is risky. Fortunately

we only found a few, and those were very dead, so the collection was

pronounced clean and hauled into the museum proper. It's currently

languishing in a sub-basement, on shelves and pallets lest there be

another flood, waiting for shelf space in the proper stores. But at

least its new packing materials will keep it safe.

In the morning we finished off what yesterday's students had worked on. We were in the museum's quarantine area, inspecting a new collection that had been donated, funnily enough, by someone who once taught me. It was boxes and boxes of Triassic synapsids, the group that gave rise to mammals, including little Diictoton that would have looked something like this:

|

| Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Diictodon-A72-01.jpg |

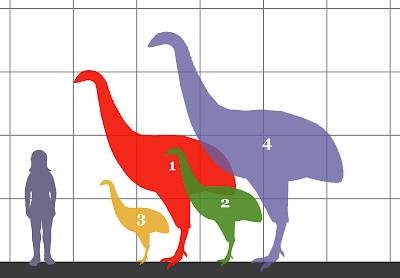

The proper location for Triassic synapsids is a cupboard in the palaeontology building that a previous curator had instead filled with moas.

|

| Classic moas vs. eagle. This eagle had a wingspan just shy of three metres. Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2d/Giant_Haasts_eagle_attacking_New_Zealand_moa.jpg |

|

| Moa sizes. Summary: would not fit in drawers. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dinornithidae_SIZE_01.png |

After we'd finished, we stood back from this cupboard and realised that there was no way the new fossils could possibly all fit in there anyway. But the collection was a little more organised than before. Success.

No comments:

Post a Comment